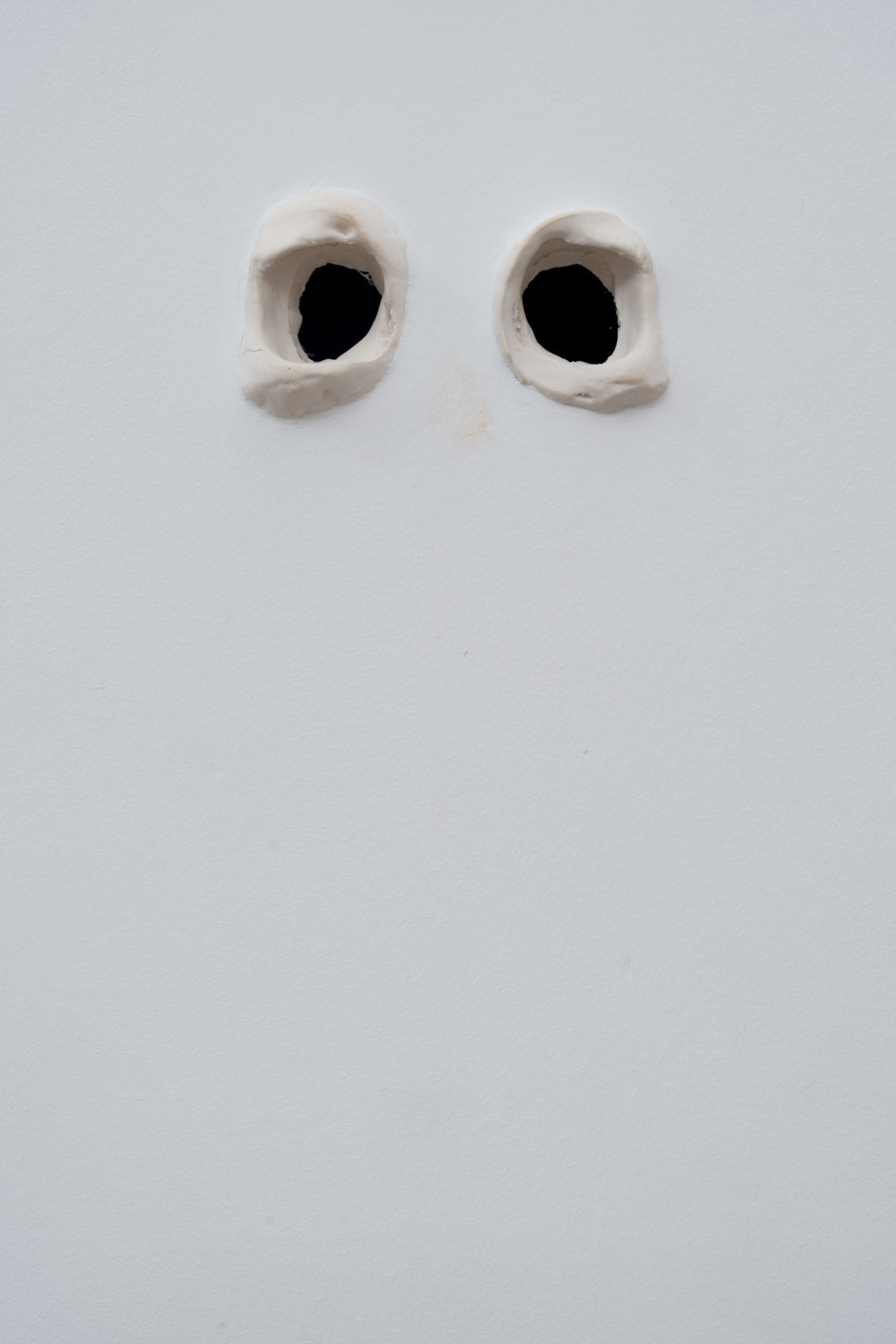

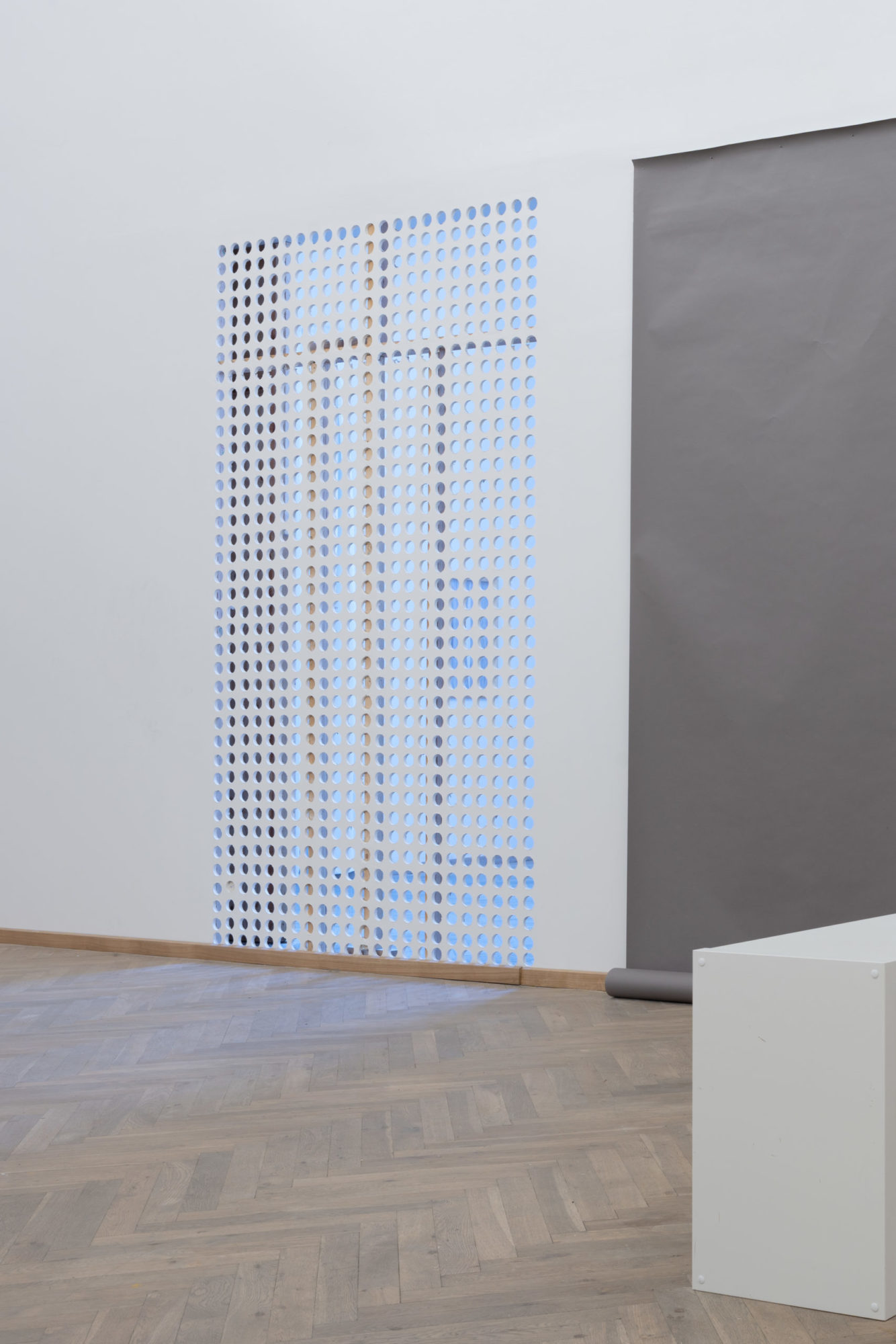

Death, 2024

Drywall, jesmonite, TV-shelf, digital projector, eyeglass lenses, camera reflex mirror, photo backdrop

Death, 2024

Drywall, jesmonite, TV-shelf, digital projector, eyeglass lenses, camera reflex mirror, photo backdrop

Working primarily with sculpture, text and images Christine Dahlerup embraces quick, sweeping gestures, flatness, and non-knowledge. Her practice is an exploration of the materiality of information, how every object, image, or sentiment is embedded with references, temporalities, and actions. The space that Dahlerup occupies produces fabulations where the ‘weightiness’ of ideas is tested, the properties of image and vision are examined, and where authorship is shared between the innateness of things, the artist, the exhibition space, and the eyes looking at the work. Dahlerup’s work for the Afgang 2024 confronts this age-old preoccupation of artists and that theme lingering above and below everything we do: Death. A TV-shelf supports a digital beamer and a small orchestrated pile of detached eyeglass lenses, with an added reflex mirror, an optical instrument used in photography to guide light beams and enable speedy image capture. Stressing this logic of mediation and the diffraction of time, the digital video projector counter-intuitively presents a looping slideshow of three black and white 35 mm analog photographs: a cryolab chamber, a close-up of a chicken’s eye, and a stylized photo of eggshells and coffee. The cryptic combination loops and starts a series of metaphoric, morphological, and metonymic chains, prompting questions about ovoid objects and membranes, life and materiality, visibility and sight, time and repetition, humans and nature, origins and generation (which came first?). Popular in biohacking, therapeutic and high-performance communities, the cryotherapy cocoon momentarily freezes the body in an attempt to counter its own deterioration, becoming a machine against the flow of time. By ‘freezing time’ and shortening distances, photography has long had a pact with fatality, it is bound to death, time, and memory. The grayscale slideshow loops at a measured pace with a pronounced and dark gap between each image, recalling the shuttering flickers of cinema, those slivers of blackness between frames that trick our perception and tie our montages and moments together. Amplifying spatial and perceptual holes as portals between one state to the next, Dahlerup has perforated a section of the Kunsthal Charlottenborg’s wall, boring dozens of holes, connecting two rooms, and letting the light in. This gesture exposes the wooden beams and underlying skeletal structure of the institution, as well as emphasizing the brittle material of drywall, this chalky gypsum underlying our surfaces. On the wall near the riddled zone, at eye-level, are a pair of cast eye sockets, the cavity in the skull which encloses our eyeballs. Dahlerup makes an architectural allusion both to the mournful and melancholic grid of Aldo Rossis postmodern San Cataldo cemetery in Modena, Italy, and the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutna Hora, Czech Republic, a gothic church decorated with the skeletons of more than 40,000 plague victims, artistically-arranged ad absurdum. After a visit to the church, Dahlerup found the skull to be the ultimate sculptural object. Molded during birth, it temporarily takes the form of a cast of the narrow part of our mother’s pelvis. It is inside of us and when we look at it, it confronts us with its facelessness. It’s just a chalky shell, a frozen non-mimic. It’s a common signifier, a memento mori. Dahlerup brings the viewer into the skull’s orbit, face to face with this sign of death, the blind supports for sight, a fundamental gap integral to knowledge.

Text written by Post Brothers

Photo credit: Carl-Christian Perch-Nielsen, David Stjernholm and Christine Dahlerup